The year is 2021. It’s the first test of the English summer. Imagine you haven’t watched a single test match or followed any news on English cricket since 2012. England has lost the toss and is batting second at Lord’s. You are tuning into the second innings of the game to watch England bat. You last remember watching Andrew Strauss and Alastair Cook open the batting for England.

Both batsmen probably weren’t the most eloquent left-handers around but they looked good on the eye and sound when it came to the basics of the game. More importantly, they were great openers for England, both averaging forty and above.

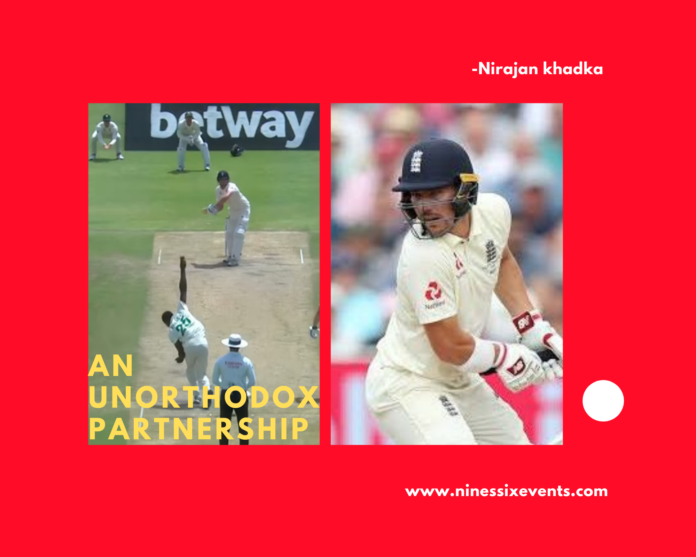

Today you see Rory Burns and Dom Sibley come out to bat, both averaging in the early thirties. You are a bit skeptical after seeing the numbers. Then you see both of them bat a few balls. Rory Burns with his idiosyncratic movements and Dom Sibley with his open chested stance. You will be justified in thinking whether these two lads are the right choice.

Well, let me regale you with a tale of these two lads from Epsom with uncanny techniques along with a rewind of the last nine years and how it shaped the current state of England’s opening spot in tests.

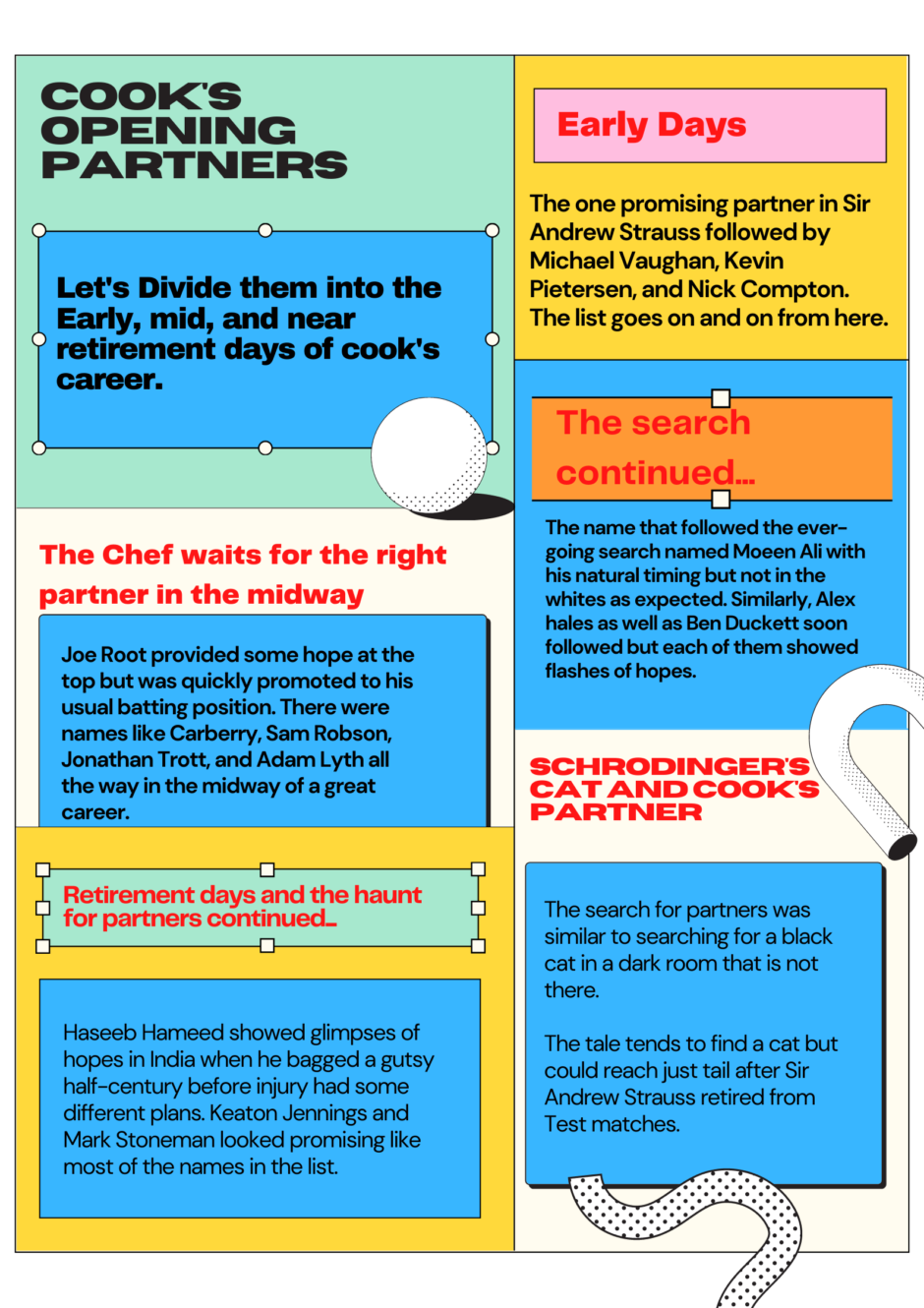

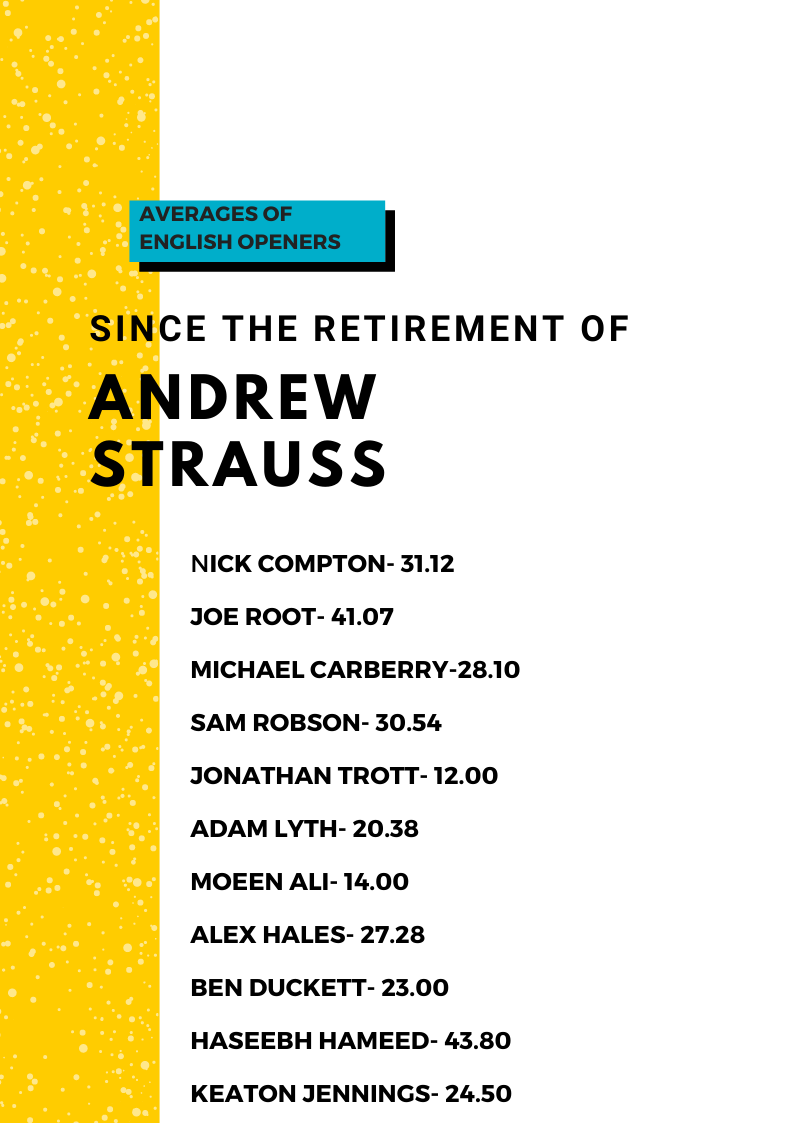

England had the luxury of two set openers until Andrew Strauss retired in August of 2012. England had to now search for a partner for Alastair Cook. Pretty easy right? Not even close. Alastair Cook batted with twelve different opening partners after Strauss retired. Yes, twelve! The most he batted with any of those dozen partners was Keaton Jennings with whom he opened twenty-two innings.

Only others with whom he opened for twenty innings were now frozen out Alex Hales and Surrey’s Mark Stoneman. Among these dozen batsmen only ones that averaged over forty while opening was Joe Root. And we all know that Root is better number 4 and way too valuable for England to be opening the innings.

The biggest problem plaguing the English test team was the selection of a stable opening partner for Cook. They never could solve it. Then in 2018, Alastair Cook retired aged only thirty-three. England, who were struggling to replace Strauss for six long years, now needed to find the replacement for Cook too.

Rory Burns was the immediate replacement for him in 2018 for the tour of Sri Lanka. After a few different options and the failure of Jason Roy in the 2019 Ashes, Dom Sibley joined Burns as an opener for the tour to New Zealand. Thus, began one of the more stable opening partnerships in recent English test sides. However, it was never plain sailing for these two unorthodox Englishmen.

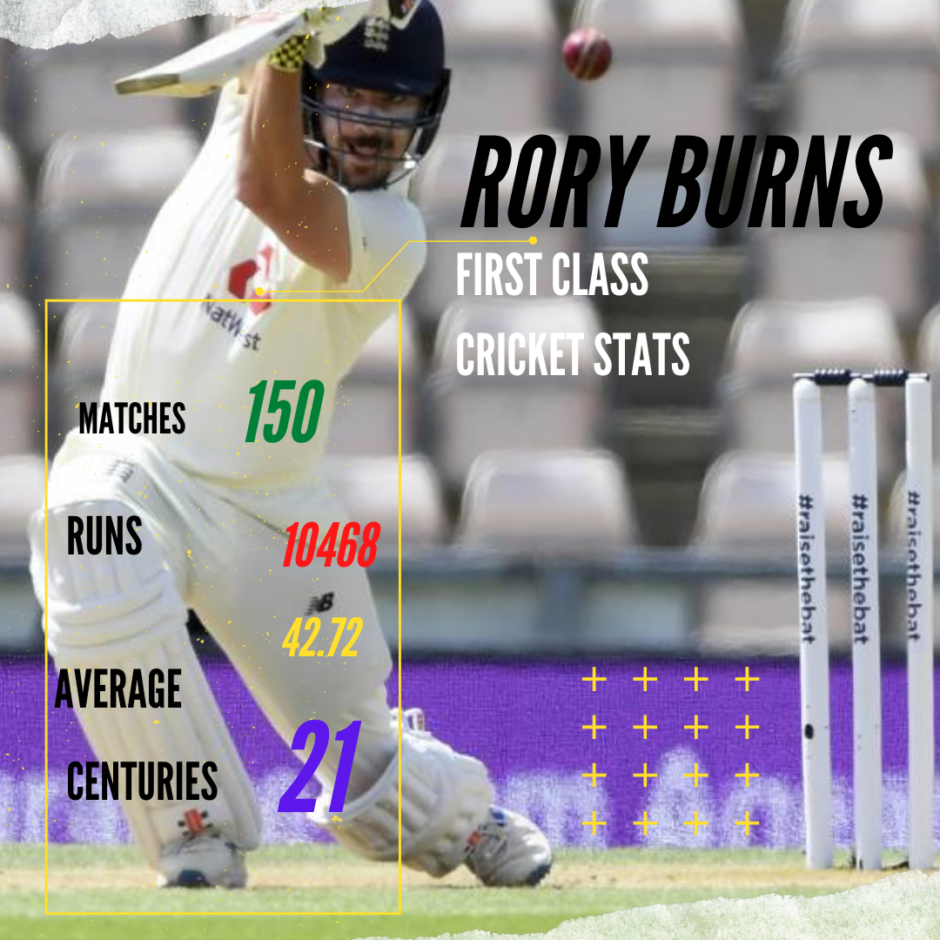

Let’s talk about the southpaw first. With all this roulette of English openers in the years since 2018, there was no way that Rory Burns wouldn’t get his chance. Selectors sometimes select players with promise rather than the best performers at the first-class level.

However, this was not the case for Burns. He made it into the national side through the sheer volume of runs he scored in County cricket. The Surrey-born lad, who made his county debut in first-class cricket in 2011 at the age of twenty-one, has continuously been the top performer in the County game since his first full season in 2012.

Currently, he captains the Surrey side with distinction and with a lot of runs behind him. He scored over a thousand runs for five seasons straight between 2014 and 2018. He also led Surrey to their first County title in sixteen years in 2018. His England call-up was a matter of when rather than if.

And in the tour of Sri Lanka in 2018, at the age of twenty-eight, he got his first taste of the international game. With mildly successful tours Sri Lanka and the Caribbean, it was the 2019 home Ashes that cemented his place in the side. With over 350 runs in the series including a determined century in the first test, he became the number one opener for England.

He may not be the most aesthetically pleasing batsman with all his movements and different stance, but with his great cover drives and the amazing ability to flick anything close to him, he had become a mainstay of the English side with future captaincy talks also making rounds.

But he had lost his place in the side during the India tour in February, which the visitors lost 3-1. However, like he always does, he went back to domestic cricket and bashed the door down for the recall as he averaged over sixty-one in the seven matches he played. And he returned to the England setup with a bang, with a great hundred in the first innings against New Zealand last week.

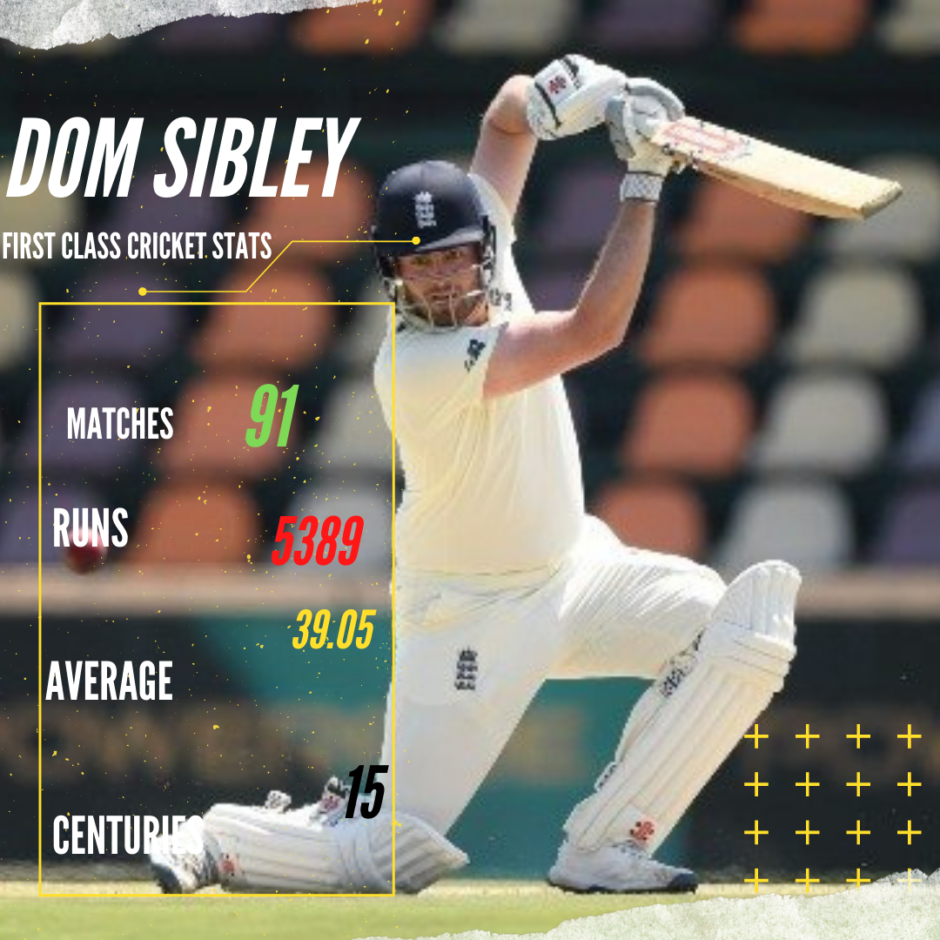

Now for his partner at the crease Dom Sibley. Born in Surrey like his opening partner, Sibley is twenty-five. A tall bulky lad who recently lost a dozen kilos to become fitter, Sibley, like Burns, deserved his England call-up on the back of his run-scoring feat.

He started his career earlier than most and made his name just aged eighteen when he scored a mammoth 242, becoming the second-youngest double centurion in first-class cricket for England. The youngest being the great WG Grace himself.

A solid old-fashioned opener who looks to bat and bat and bat, Sibley made his debut in the New Zealand tour in late 2019. After Jason Roy’s Ashes horror show, England was looking for a partner for Rory Burns. Though, Sibley probably wasn’t the type of opener English selectors were looking for (we’re looking for a more dominant opener), but his numbers couldn’t be ignored anymore. In 2019, he scored 1,324 runs in domestic first-class games at an astonishing average of 69.68.

Bear in mind, he was the only batsman to cross 1000 runs in the championship that year. After leaving Surrey to join Warwickshire in 2017, he faced a period of hard times. But after making some change in his technique with the help of Gary Palmer in 2018, he became a force who couldn’t be overlooked.

His technique raised a few eyebrows as he failed to make an impact in New Zealand. However, he had a great tour of South Africa, where he played a big hand in beating the Proteas, with an average of over 50. He also scored his maiden test ton in that series. Since then, he has been inconsistent, to say the least.

However, his ability to occupy the crease to grind out ugly runs and great potential seems to make him one of England’s most promising openers in recent time.

So, how do they fare in partnerships? They started very well with a half-century stand in their first test innings together. They averaged nearly equal to the Strauss-Cook duo in their first four tests.

They are relatively a new couple as they have only opened 13 test matches which include 20 innings. They average a modest 30.05 in those twenty innings but some of those innings were on some of the tougher Indian and English pitches in recent times.

They face 75.3 balls per innings together for the first wicket which is a very promising sign and an improvement on most previous test match opening pairs since the famed duo of Strauss and Cook. Burns and Sibley have five stands crossing 50, including a century partnership against the Windies last year.

Their solitude in the crease is more showcased by their individual stats. Rory Burns plays 74 balls per innings on average with 1448 runs in his 44 innings for England. With an average of nearly 33, which is the third-highest among England openers since Strauss, for those who have played more than 5 innings. The only ones who rank higher are Cook and Joe Root. Dom Sibley is the fourth on the list with an average of 31.4.

The average number of balls faced by Sibley is even more impressive. He faces 82 balls per innings on average. The only person that can better Sibley’s record in the present English side is the captain Joe Root himself. Alastair Cook, who was probably the greatest batsman in English test cricket history, averaged 91 balls faced per innings and Strauss faced 81 balls on average.

Even when compared with these two great openers, the record of Burns and Sibley is decent. Sibley and Burns have two and three hundred to their name respectively. So, although the stats do not jump out to you, the underlying numbers are good. And if they can show some consistency then I believe they are the right choice for the job.

There are some criticisms and arguments about the techniques of these two. Being their own kind of batsmen with unconventional styles, it is easy for people to point it out. We can clearly see how uncanny they look in the crease. They aren’t the most fashionable cricketers around. Burns with his thousand moving parts and Sibley with his chest-on approach to batting along with his bat coming almost from point region, it can be different to the eyes. But apart from a few flaws against spinners, which let’s be real all English batsmen have apart from Joe Root, they are technically sound.

Burns’ so-called troubles with the short ball are not so much technical as it is a problem of approach. And Sibley’s arc of the bat while playing a shot can be fixed easily. His way of handling the bat reminds me of Cook who also floated it around while batting. Along with his hunger for runs and him being happy to grind out runs the hard way, he, in my opinion, is a lot like the Chef. If he even has a career that is even half of what Cook had, I think we are in for a treat.

Maybe it’s because of the condition of opening slots in limited-overs cricket in England, where they have a wealth of world-class options, that has led to the opening slot in test cricket put in more scrutiny. Along with this, the allegations about Sibley and Burns batting too slow aren’t helping their case. People have become accustomed to the stacking approaches to batting, even in the longest format.

Openers like David Warner and Rohit Sharma have spoilt us with mouth-watering innings in test cricket. So, there is this stigma towards players like Kraigg Brathwaite, Cheteswar Pujara, and the English openers in being too slow. It doesn’t help that Sibley has the strike rate of thirty-five (yes! Thirty-five) and Burns strikes at less than forty-five but they shouldn’t be judged on that too much. It’s the job of the openers to see out the new ball and blunt the opposition attack, which they are good at doing.

Their solidity allows busy players like Ben Stokes and Jos Buttler to flourish in the side. The English press is particularly harsh on its sportsmen, but I don’t think they should be much fussed about something being slow and time-consuming, Brexit has them covered in that part.

I believe the careers of these two lads from Epsom will greatly affect the coming years of English test cricket. If they go on to have decent careers, I seriously think England can dominate the test arena for the next five years. But if the opening spots remain unstable, well it’s pretty much the same old case of under-performing by the team.

If anyone is capable of stabilizing the English top-order, these two unconventional batsmen from Surrey are the ones in my opinion. And if they live up to their promise and the backing of the selectors and captain, I believe the near future of English test cricket is in safe hands.